译者:傅春雨 @boattractor_cj

文章来源:《文化人类学》(Cultural

Anthropology)学刊特刊

标题:On

“Terrorism” and the Politics of Naming

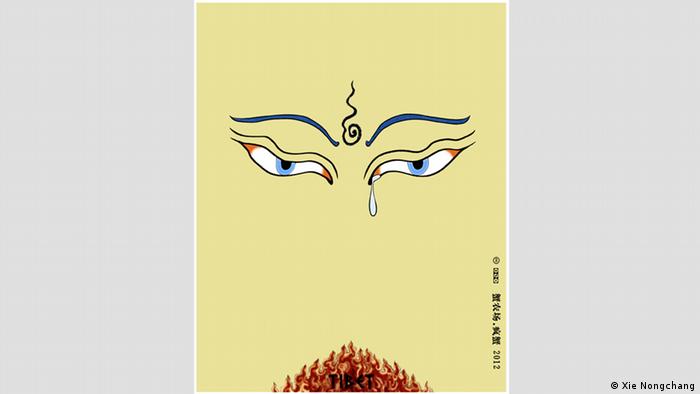

“尽管我理解他们的绝望,但这样的自我戕害是完全背离佛教基本教义的。”一位经常去西藏旅行的美国朋友如是评论道。他的说法代表了一种普遍的情绪。中国政府也作如是争辩。究竟该怎样看待藏人自焚?许多人不禁要追问(不同于自杀炸弹攻击曾被本能地,当然也是错误地,认为渊源于伊斯兰教)一个最首要、最根本的问题:那些自焚者是否背离了他们信仰的宗教?认为背离了的观点最近引起许多学者的争论,尽管在西藏并无先例,但自焚作为一种牺牲奉献,或更为广义的,为崇高事业而自我牺牲,在佛教上却是有悠久历史的。

在双流机场,我告诉出租车司机要去武侯祠(在成都的一个藏人聚居社区附近)(原注1)一个我常住的旅馆,“别去那儿,”他立即劝道:“那儿不安全,实话告诉你,满街都是藏人,到处都是警车,没好处。”他试图说服我去别处,我不肯,他则不再说话。当我们来到武侯祠附近,他指着路边一辆又一辆闪着警灯的警车,“看见了吧?”对我说道:“跟你说了的。”“但是,怎么个不安全?出了什么事呢?”我问道。“这条街都是藏人,”他回答,仿佛这就是充足的理由,“谁知道呢?你明白,他们有枪和其它玩意儿。”

这些自焚者在什么程度上,希望人们把他们的行为理解为政治抗议或宗教献身?他们是受到“阿拉伯之春”的鼓舞而行事?还是在效法释广德(

译注1)的自焚?他们知道这些事件吗?或许,他们是在有意识地寻找、创造一种新的,不同于2008年发生在西藏的抗议形式?这些问题值得提出。但同时也应意识到,从一定程度上来讲,个人自焚行为(的动机)是很难彻底搞清楚的,这不仅因为目前广大藏区处于隔绝状态,而且也因为自杀本身的特性所限。

藏人对自焚的反应也不尽相同。“我觉得这不是一个好办法,”一位学者评论说。“人些都疯了,政府也疯了。我们再也不知道该怎么想,该怎么做了,”一位当地的知识分子,也是广受尊敬的僧人对我说。另一位藏传佛教的学者悲伤地评论说,他认为新的噶伦赤巴(译注2)称自焚者为藏人英雄是起了一定作用的。“谁也不知道最初几起自焚事件的具体情况是怎样的,但现在人人都在说他们是英雄。他们以为他们在做事情,但现实的结果却是原来仅剩的一点空间也被堵死了。”但另一位观察者却这样说道:“他们给了我们勇气。谁也不会认为自焚会马上会给我们带来独立。但这种方式能让世界了解到底发生了什么,让世界知道真相。”所有人都同意一点:不管怎么说,近期发生的事情和眼下当局在藏区实行的统治方式脱不了干系。

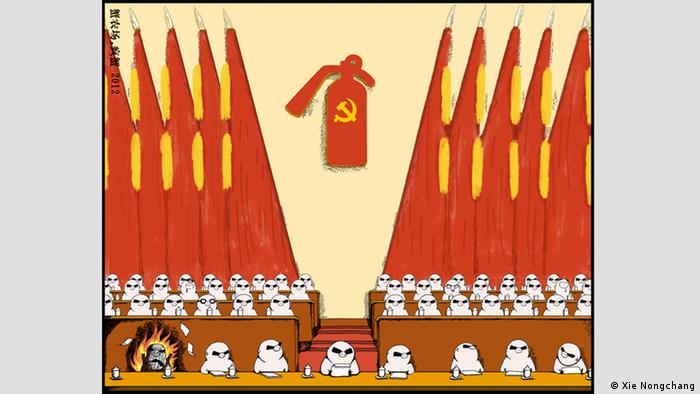

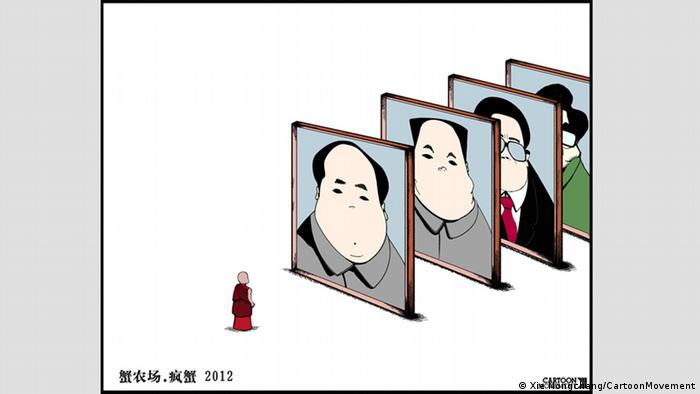

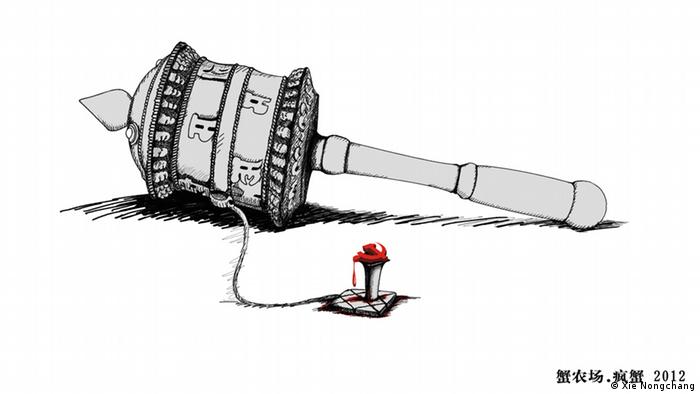

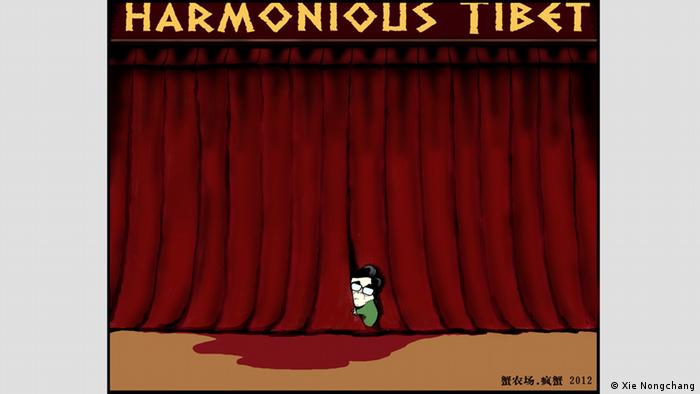

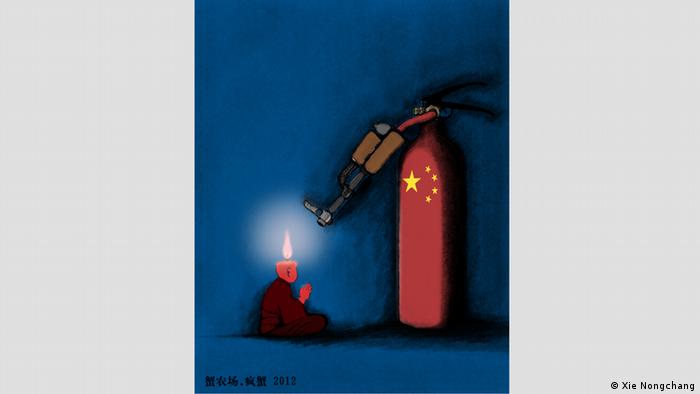

与其再进一步探究自焚者的确实动机,我更宁愿分析这些事件是怎样被不同方面定位、看待的。尤其是,我特别感兴趣为什么中国政府要给这些行为贴上“恐怖主义”的标签。我必须明确声明:我不认为自焚是恐怖主义行为。既然这种行为不会给其他无辜者带来任何伤害,为什么会被如此标注呢?一个显然的答案是,正如斯图尔特·埃尔登(Stuart Elden)所指出的,“恐怖”和“领域”之间的关联绝非偶然(译注3)。要维持一个边界之内的领域需要不断的运用威慑。几乎所有是被美国国务院列出的恐怖组织都是自有其宗旨的活动团体。在美国,这些团体为维持其信条所界定的领域而行使的权威,分割了美国政府之领域的权威。同理,“反恐战争”(Elden, 2007), 以及现在中国将藏人自焚标注为“恐怖主义”都表现出了另一种形式的权威分割,产生了各自分裂的目的和不同的方法。在这种新的架构下,政府将任何视为对其领域权威的挑战,无论其方式和实际影响是否伤及他人,一概宣布为“恐怖”活动。

“看看这地方,”他说道,“这不是武侯祠(Wuhouci),这简直就是武警祠(Wujingci 原注2)。你可以在这里检阅所有类别的人民武装警察,以及他们的各种武器装备。”政府如此不加掩饰的紧张、担忧让人难以理解。因为很少人庆祝洛萨(译注4),干部,单位职工和大专院校被要求购买烟花爆竹以制造节日气氛。但在光天化日之下,这个繁华大都市城区一角的气氛却仍然像是被占领的巴格达。不准拍照。每隔一百米就有闪着警灯的车、保安的小车、面包车和大巴士。制造欢乐气氛的念头终究还是敌不过更强烈的、以安全为名而实施强压的思维。

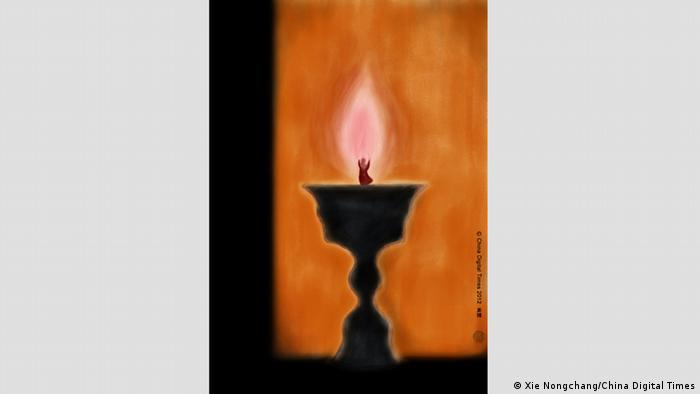

比恐怖和领域的联系更直白的事实是:国家-政府不容许自杀,只容许处死。正如塔拉勒·阿萨德(Talal Asad)所提示的,个人没有权力自杀,只有政府(和上帝)才能授予人们被处罚(或处死)的权力。因而,未被国家-政府所批准的死亡,“一个不受胁迫的自我能够挑战体制的惩诫权威的场景”(Asad, 2007:91),显得很具威胁性。自2008年以来,在所有藏区实施的封锁已经宣判了所有藏人一如既往的有罪,将他们置于一个“乱世用重典”的特区;在这个特区中,重典的力度就是一切,根本无需区分什么是犯法,什么是冒犯权威(Agamben, 1998:27, 32)。这更加彻底地剥夺了藏人政治表达的权利,正如汉娜·阿伦特(Hannah Arendt)很早以前所指出的那样,该权利是人之可能成为独立个体的根本基础,而只有能够成为独立的个体,人才称之为人。从这个意义上讲,自焚就是在(如前面所说的)封锁状态下重申自己的个人主权。一个生物学意义的生命奉献于一个政治生命的宣言。正是这种含义的现实性,吓得政府赶紧去强化它的领域权威。

原注:

1:四川首府成都既是进入川西北藏区的门户,也是去到西藏自治区境内的拉萨的重要交通枢纽。

2:武警(Wujing,汉语拼音)是指人民武装警察。武侯祠(Wuhouci,

汉语拼音),纪念武侯的祠堂,是成都一个藏人聚居的社区。

参考文献:

乔治·阿甘本(Agamben,

Giorgio), 1998, “神圣的人:自主之权威”(Agamben, Giorgio. 1998. Homo

Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford: Stanford University Press.)

塔拉勒·阿萨德(Asad,

Talal), 2007. “论自杀炸弹攻击”(Asad, Talal. 2007. On Suicide

Bombing. Columbia University Press. )

斯图尔特·埃尔登(Elden,

Stuart),2007, “恐怖与领域”(Elden,

Stuart. 2007. “Terror and

Territory.” Antipode.

39(5):821-854.)

译注:

1:释广德(Thich Quang Duc ),前南越和尚,1963年6月11日在西贡(现胡志明市)闹市自焚以抗议吴庭艳(天主教徒)政府对佛教的歧视政策。他自焚的照片在西方引起极大关注和同情。后来有更多和尚效仿自焚,引起南越政局恶化,西方对吴庭艳政权的反感,并最终导致吴庭艳在政变中身亡。

2:噶伦赤巴:藏语,即西藏流亡政府总理或首席部长。

3:英语“恐怖”(terror)和“领土,领域”(territory)源于同一拉丁词根terr。

4:洛萨(Losar):藏语,藏历新年。

On “Terrorism” and the Politics of Naming

Emily T. Yeh, Department of Geography,

University of Colorado-Boulder

“While I understand their desperation, this

kind of self-damage seems a very far cry from the fundamental tenets of

Buddhism,” observed an American acquaintance who frequently travels to Tibet.

His is a common sentiment. The Chinese government makes this argument too. What is it about Tibetan self-immolation that

leads—in an inverse of suicide bombing, reflexively and incorrectly read as a

transhistorical Islamic act—so many to question first and foremost whether

those who have engaged in it have turned against their own religion? Such claims have led numerous scholars to

argue recently that, though unprecedented in Tibet, self-immolation as

sacrifice and more generally, self-sacrifice for a noble cause, has a long

history in Buddhism.

I gave the taxi driver at Shuangliu airport

the name of the hotel in Wuhouci, the small Tibetan neighborhood in Chengdu

[1], where I often stay. “Don’t go

there,” he immediately advised, “The security is bad. I’m telling you the

truth. That entire street is full of Tibetans. Everyone there is a

Tibetan. There are security vehicles

everywhere. It’s no good.” He tried to persuade me to go elsewhere and

fell silent when I refused. As we

arrived, he pointed out the police car with flashing lights by the side of the

road, then another, and another. “See?” he said, “I told you.” “But why is the

security bad? Did something happen?” I asked. “This whole street is full of

Tibetans,” he said, as if he had offered an adequate explanation. “Who knows?

You know, they have guns and stuff.”

To what extent do those who self-immolate

mean for their acts to be understood as political protest and/or religious

sacrifice? Were they inspired by the Arab spring? By Thich Quang Duc’s

self-immolation? Did they know about these? Or rather, were they deliberately

and creatively searching for a new form of protest different from those that

transpired in Tibet in 2008? Such questions should be asked. But at the same time, individual acts of

self-immolation are in a sense ultimately unknowable, not only due to the

sealing off of many Tibetan areas at present, but also due to the very nature

of suicide in general.

Tibetan reactions vary. “I don’t think it’s

a good method,” remarked one scholar. “The people have gone mad. The government

has gone mad. We don’t know what to think or do anymore,” a local intellectual,

a respected monk, told me. Another, also

a learned scholar of Tibetan Buddhism, remarked sadly that he thought the new

Kalon Tripa’s calling them Tibetan heroes played a role. “Who knows what the

circumstances of those first few individuals’ actions were, but now everyone

has spread the word that they are heroes. They think they are doing something,

but all that is happening is a closing down of what little space remained.” But

another observer says, “They’ve given us courage. No one thinks that self-immolation will lead

immediately to independence. But this is a way of letting the world know what

is happening, so that the world can see the truth.” All agree that, whatever

else, the recent events cannot be divorced from the forms of governance

currently in place in Tibetan areas.

Rather than probe further into motivations,

I look instead at how the acts have been interpreted. In particular, I am

interested in why the state labels these acts of terrorism. Let me be clear that I do not consider

self-immolation terrorism. Why, given

the absence of any harm to innocent others from these acts, are they thus

labeled? One obvious answer is that, as Stuart Elden has pointed out, the

linkage between “terror” and “territory” is hardly coincidental. Maintaining bounded spaces of territory requires

the constant mobilization of threat.

Almost all groups on the US State Department’s list of terrorist

organizations are self-determination movements. Just as the tenet of

territorial preservation of existing boundaries has become split from internal

territorial sovereignty in and by the U.S. War on Terror (Elden, 2007), the

labeling of Tibetan self-immolation as “terrorism” in China today performs

another kind of splitting of sovereignty, creating a disjuncture of methods and

aims. In this new formation, the state

declares a form of terror any perceived threat to state territorial

sovereignty, regardless of its actual methods or effects vis-à-vis harm to

others.

“Look at this

place,” he said. “It’s not Wuhouci. It should be called Wujingci.[2] One can survey all kinds of People’s Armed

Police here, their manifold weapons and techniques.” The government’s

preoccupation with appearances is puzzling.

Because so few Tibetans were celebrating Losar, cadres and work units

and universities were ordered to buy firecrackers and put on festive

appearances. Yet smack in the downtown of the bustling metropolis, a few

streets take on the appearance in broad daylight of occupied Baghdad. No

photography allowed. Flashing lights and

paramilitary cars, vans, and buses every hundred meters. The drive to happy appearances is finally

conquered by the even greater drive to suppress in the name of security.

Beyond the relation between terror and

territory is the fact the nation-state does not allow for suicide, but only

authorized death. As Talal Asad reminds us, individuals have no right to kill

themselves; only the state (and God) gives them the right to be punished (or

killed). What appears terrifying, then, is a death unregulated by the

nation-state, “the illusion of an uncoerced interiority that can withstand the

force of institutional discipline” (Asad, 2007: 91). The state of siege enacted throughout Tibetan

areas since 2008 interpellates Tibetans as always already guilty, positioning

them in a zone in which “violence passes over into law and the law into

violence,” where what matters is the pure force of the law rather than any

actual distinction between the forbidden and the authorized (Agamben, 1998:27,

32). More than ever, this has denied

Tibetans the right to act politically, which Hannah Arendt long ago suggested

is the basis of the possibility of being individual and thus human. In this

sense, self-immolation is a reclamation of sovereignty over one’s own self

within a state of siege. Biological life is taken in an assertion of a

political life. It is this possibility

that is terrifying to the state in its quest to stabilize territorial

sovereignty.

24 March 2012

NOTES

[1] Capital of Sichuan province, Chengdu is

a gateway to the Tibetan regions in northern and western Sichuan, as well as an

important transportation hub to Lhasa in the Tibet Autonomous Region.

[2] Wujing refers to the People’s Armed

Police. Wuhouci, or Wuhou Temple, is a Tibetan neighborhood in Chengdu.

REFERENCES

Agamben, Giorgio. 1998. Homo Sacer:

Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Asad, Talal. 2007. On Suicide Bombing.

Columbia University Press.

Elden, Stuart. 2007. “Terror and

Territory.” Antipode. 39(5):821-854

延伸阅读:

《文化人类学》(Cultural Anthropology)关于藏人自焚之特刊 http://woeser.middle-way.net/2012/04/cultural-anthropology.html