Red Guards in Tibet12 min read

Robert Barnett and Susan Chen talk to Tsering Woeser

Ed: In her new book Forbidden Memory: Tibet During the Cultural Revolution, Tibetan author Tsering Woeser dissects the impacts of China’s Cultural Revolution on Tibet. In this interview the book’s editor, Robert Barnett, together with its translator Susan Chen, speak with Woeser about the English-language version of her book and the enduring significance of the photos taken by her father, Tsering Dorje. Later this week we will also be publishing a photo essay featuring a selection of Dorje’s photographs.

When Tibet was taken over by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in 1950, the Chinese officials sent to run Tibet initially made few changes to its society, culture or administration. But, as with most revolutions since the 18th century, in time the Chinese Communist project in Tibet turned to the use of terror. Initially, this took the form of Robespierrean public education – mass imprisonment and executions – but by the mid-1960s the dominant form of political violence had become the ritualized humiliation of teachers, scholars, landlords and others whom the revolutionaries identified as their enemies. These “struggle sessions” and “speaking bitterness” events, along with ultra-leftist policies, factional conflict, and rebellions, were defining features of the Cultural Revolution in both Tibet and China from May 1966 until the death of Mao in September 1976, ten years later.

In the early 1980s, the Party itself condemned the Cultural Revolution and allowed many Chinese writers to record their experiences. However, first-hand accounts of that time by Tibetans who remained within China are almost non-existent. Only a handful of refugee reports attested to what had happened when the Cultural Revolution was exported by the Chinese to a totally distinct culture in what was, in effect, a colony.

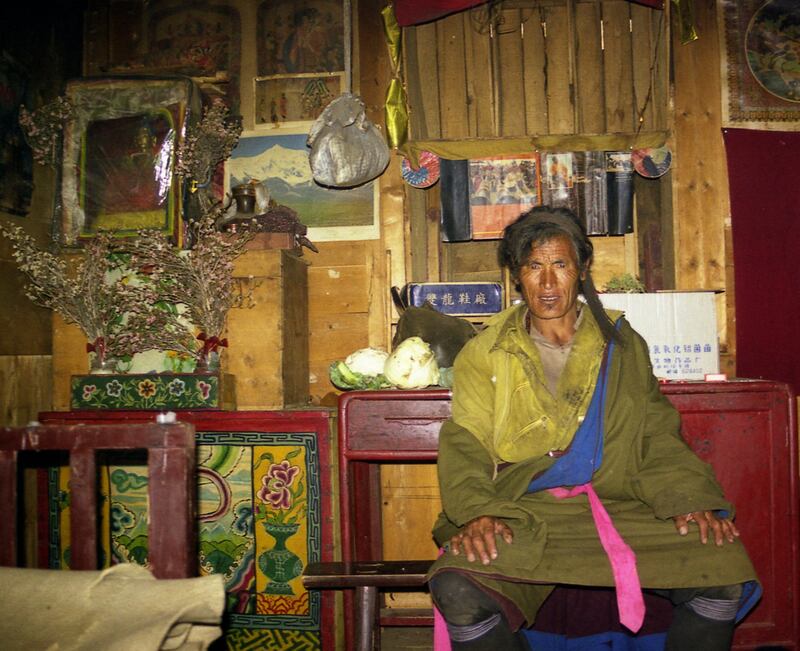

In 1999 this situation was transformed when Tsering Woeser, a Tibetan poetess and dissident essayist living in Beijing, began to study a set of photo negatives that her father, who had served as a PLA officer and photographer in Tibet until his death in 1991, had left with the family. The photographs included hundreds of images of events in Tibet during the Cultural Revolution. Over the next six years, Woeser interviewed some seventy Tibetans and Chinese who had witnessed those events, showing them her father’s photographs and documenting their responses. None of this work could be published within China, but in 2006 the Taiwanese publishing house Locus produced Shajie (殺劫), Woeser’s book-length essay in Chinese about these interviews, together with 300 photographs, extended captions, and analysis. For the first time, the world saw uncensored images showing how the Cultural Revolution had been carried out in Tibet.

Three years after the Chinese edition of her book appeared, Woeser, myself, and the translator Susan Chen began work on an English-language version. We revised and updated the text, added new information to the captions, and included a postscript by Woeser on the changes in Lhasa since her father took his photographs. The result, Forbidden Memory: Tibet During the Cultural Revolution, was released by the University of Nebraska Press earlier this summer. For the China Channel, we asked Woeser to look back at that process and to reflect on the significance of her father’s photographs today. – Robert Barnett

Robert Barnett and Susan Chen: Forbidden Memory is a unique record of an episode in Tibetan history some fifty years ago. How would you describe that episode, and what did you learn about it that was not known before?

Tsering Woeser: The most important insight that I drew from the 300 or more of my father’s photographs that I’ve put in Forbidden Memory was about the amount of damage done to monasteries, Buddhist statues, and texts, as well as the name changes that were imposed on places and buildings. These are all so important to traditional Tibetan culture and history. There was also the abuse and humiliation that the photos showed. This was done to Tibetan high lamas, aristocrats, officials from the former government, wealthier merchants, doctors of traditional medicine and others – even though many of them had collaborated publicly with the occupation forces of the PRC. The photos show the form of rule that the Chinese Communist Party imposed on Tibet – what I would call military imperialism. To me, these were realities that had been hidden. They were buried pains and sorrows.

The state narrative is that this was all caused by Tibetans themselves. On the surface, this is true, and you can see some of that in my father’s photos. However, when I interviewed people who actually remembered the violence in those photos, and when I dug into the official publications and internal documents, I realized that many facts have been hidden by the Party. Through writing the original and now working on the English version, I have learned also that, however powerful they are, the authorities cannot arbitrarily rewrite history.

Apart from documenting Tibet’s recent history, what makes the book significant for today’s readers outside Tibet – particularly for those who are interested in learning about China, but whose knowledge of Tibet is limited? What relevance and what insights do you think it might offer to them?

Forbidden Memory makes it impossible to deny that the Cultural Revolution was catastrophic in its impact on Tibet. It was certainly destructive all over China, but in Tibet, it exacerbated the damage done by the Party during the PLA’s occupation in the 1950s. The devastation of the Cultural Revolution was far-reaching and traumatic in terms of how it affected Tibetan culture, beliefs, economy, and society. You can see it even now with, for example, the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa or Ganden Monastery just outside the city. They have been renovated or rebuilt so that, on the surface, their prior destruction is no longer immediately visible. But it’s generally agreed among critical scholars and intellectuals that Mao’s death in 1976 didn’t bring an end to the Cultural Revolution in Tibet like it did elsewhere. Many Chinese and Tibetan officials in Tibet whose careers were made during the Cultural Revolution remained in high positions, and their efforts at self-promotion have only continued. They have now become political role models for younger opportunists. They may look very different on the outside from their “revolutionary” predecessors, but many of the things they have done are patterned on what activists did when they followed Mao’s directives in the Cultural Revolution. These activities are what we see in the photos in Forbidden Memory.

Could you talk more about the similarities and differences you noticed between official behavior during the Cultural Revolution and official behavior today?

You don’t see today’s officials directly attacking Tibet’s cultural tradition in the way the Maoist activists did during the Cultural Revolution, but there are huge propaganda hoardings on mountain slopes and hillsides all over Tibet. The portraits of CCP leaders from Mao to Xi Jinping are put on the walls of monasteries and private homes, and the Chinese national five-star flag flies from the Potala Palace [the Dalai Lama’s palace in Lhasa]. This is all the logic of “cultural revolution.” It permeates every corner of Tibet today.

You researched and wrote the first version of the book over a decade ago. What has changed since then? If you were starting again now, what would you do differently?

Before I worked on Forbidden Memory, my writing was mainly poetry and imaginative prose. This has deeply influenced my nonfiction writing. I embed poetic aspects of my work in narratives of specific events, identifiable places, and connections between the past and the present.

I have watched carefully the changes in Lhasa and other places in Tibet. Overall, despite repackaging by the state, I see the Cultural Revolution as still ongoing in Tibet, albeit in a much less obvious version. You can see it, for example, in the current official project to “renovate” Lhasa in the name of “modernization.” The city has been drastically remade so as to rewrite history, to encourage Tibetans to take on a Chinese identity, and to promote commercialization and Han immigration. The old city of Lhasa was closely bound up with Tibetans’ spiritual and secular lives; now it has become an exotic theme park for tourists. Any presentation or expression of Tibetan culture or history has to be shown as a subset of “Chinese values” or it won’t be allowed.

To start the project for Forbidden Memory again now? I think I would want to deepen my understanding of every theme and detail that emerges from my father’s photos. I would want to say more to contextualize what happened to particular individuals. The major obstacle now would be finding people who experienced and remembered the Cultural Revolution. In the late 1990s and the early 2000s, I was able to find more than seventy of them. Some of them were activists involved in the attacks, and others were victims or unwilling participants. More than half of them have died since then. Without them, or strictly speaking without the memories they related to me, it would be very hard to write this book. They are the true authors here.

Their spiritual world is full of scars, trapped inside a gigantic net built by the Chinese state”

In many ways, Forbidden Memory is about your efforts to understand the feelings and thinking of the former political idealists and activists you interviewed. What did you learn about political zeal, and about subsequent rethinking and regrets, from your interviews for the book? How did this affect the way you have come to see the Maoist era in general?

The activists and idealists are my elders – my parents, my parents’ siblings and their spouses, my teachers in school, and my superiors and senior colleagues where I used to be employed. Some of them I have known since I was a child, others I was close to as a young adult. From what I was able to hear and observe, sometimes even without directly talking with them, I could understand the actions and the thinking of their generation. Rather than say that they were political idealists or activists, I think, more precisely, many of them are what I would call “double-thinkers”. Only a minority of them, my father included, might have been genuinely idealistic about the political principles they said they believed in. Yet, whether they were idealists or not, the lives they lived were full of tragedy. The more I tried to understand them, the more I realized how they had been engulfed, destroyed, wasted by the regime in so many inhuman ways.

I once wrote about this – that an entire generation of them (and perhaps more than just their generation) are a unique outcome in history. For decades, their lives were so entangled with political turbulence over which they had no control that they metamorphosed into a kind of extreme dependency, a kind of parasitism. Their spiritual world is full of scars, trapped inside a gigantic net built by the Chinese state. Most of them can do nothing but follow its momentum. They are now fragile and old. Looking at their faces – Tibetan, familiar, but marked with confusion and alienation – makes me feel deeply saddened. I feel an almost inexpressible aversion to the monstrous state that has controlled and manipulated their spirit.

The photos your father took in Lhasa and in the Kham region of Tibet during the Cultural Revolution are central to Forbidden Memory. Has his photographic work and the history you discovered helped you understand him and Tibetans of his generation who were part of the Cultural Revolution?

Yes, I didn’t publish the photo of my father in his army suit until 2016, when the second Chinese edition of Forbidden Memory came out. It has not been easy for me to talk about him publicly. My father had a long career in the Chinese army. At a time when joining the army was somehow seen as an honor, he enlisted when he was 13 in the 18th Army, the part of the PLA which first went into Tibet and ran the occupation in the 1950s. When he suddenly fell ill and died in 1991, he was 54. He had been with the army for 41 years. By then, he was a deputy commander of the PLA forces in Lhasa. I remember that at least once he refused promotion to a civilian position simply because he was unwilling to let go of his military uniform. And yet he took photos of the disasters that the CCP brought to his beloved homeland. I cannot help but wonder: Why did he take these photos? Why did he preserve them so carefully?

It seems to me now that he was very intentional in using his camera to document what was happening. I talked about this with my mother. She thought that my father was simply zealous about photography. “He took photos of everything,” she said. I didn’t completely agree with her. But I was only 25 when my father passed away. I was too young, too immersed in my own far-from-reality universe of poetry and art to have asked him about the photos he’d taken. That’s been an irreversible regret for me. Some twenty years after he died, I began to use his camera to take photographs in many of the same locations where he had taken his photos. Those are in the book as a Postscript. But who was he keeping records for? I am not him and I can’t speak for him, but I know that if he was still alive, he wouldn’t be content with the current order of things in Tibet – though I’m sure that he wouldn’t have become a dissident, a “traitor,” like me.

I have often imagined that if military service had not been his profession, my father would have chosen to be a professional photographer. But it was his destiny to be a professional soldier instead. It’s the same destiny that has connected me with his photographic work – as if he had kept those photos for me to complete a puzzle about the saddest chapter of Tibetan history as it happened. ∎