我:印度确实是一个很复杂的国家,多民族多宗教。你说印度战略方面的人不希望喜马拉雅藏传佛教化,然而这个世界上并不是只有军事才是权力,经济才是权力,不是啊。你有枪你就权力最大,或者你有钱你就权力最大,不一定的。从人类历史来看,宗教是跟人的精神、人的灵魂有关的这样的一个更大的权力,是生生世世的,是可以跟武器抗衡的,可以跟金钱抗衡的。信仰的权力是无形的,也无法估量的,不然的话,全世界多少国家的政权更替,政客轮换,有枪又怎么样,有钱又怎么样?而宗教信仰一直都存在,佛教都几千年了,基督教伊斯兰教也都是啊。

另外我还想到,前不久应该是三月期间在达兰萨拉有一个很重要的法会,是嘉瓦仁波切专门给蒙古来的信徒灌顶,哲布尊丹巴的转世灵童正式出现在灌顶法会上,而且还被特别授权主持了其中关键的仪式。实际上嘉瓦仁波切在蒙古信徒的心中,还有布里亚特、图瓦、卡尔梅克等蒙古地区的信徒心中也很重要。那么被污名化这个事件有没有在那些信徒当中产生什么反响呢?不过我们现在还不知道。布里亚特那些地区与俄罗斯这样的极权国家的关系注定也是敏感地区,而且现在处于俄乌战争中,很多人在战场上丧命,被认为是普京对少数民族的清洗。

朋友:蒙古国家及蒙古人地区我是比较了解的。也是比较复杂的,跟历史有关。他们受到了共产主义思想的影响。毕竟被共产主义苏维埃统治了七十多年,两代人没有受到佛教文化的教育。但是他们也有历史的记忆。佛教文化对于他们来说是非常重要的。基本上,蒙古有三种人,一种认为蒙古不需要佛教,蒙古只有成吉思汗,成吉思汗决定一切。部分人认为我们是佛教徒,但我们是蒙古人,所以我们是蒙古佛教徒,而不是藏传佛教徒。蒙古人里面的藏传佛教徒的影响不大。当然还有一些人是信仰其他宗教的。

蒙古人分布在两个国家中,一部分在俄罗斯里,一部分在蒙古,因为跟中国的关系,从经济和政治考虑,很多话不会说,不愿意说。而且,因为七八十年没有佛教,现在虽然慢慢地有了,但很多人还是困惑的,找不到自己的道路,这一点与蒙古的学者交流的话可以了解到,他们有不安全感,他们不知道该去往哪里?所以蒙古不会对尊者的事件有什么反应,这是可以理解的。

问题不是蒙古是否该有反应,或者会不会去街头游行。问题在于别的。正如前面我说过的,首先,从人的角度来说,达赖喇嘛他没有错。这个是事实,这个现在已经是全世界公认的了。无论是宗教界的人士还是学者,比如心理学家人类学家等等都认为达赖喇嘛没有犯错。当然有人认为他错了,这就成了一个挑战性的问题。一个人没有犯错,但是却被认为犯错了,那么怎么解决这个问题?这成了一个很大的问题。对于包括藏人以及喜马拉雅地区的信徒来说,达赖喇嘛原本就是一个喇嘛,一个地位很高的喇嘛,但现在成了另外一个层次的喇嘛,成了一个活生生的菩萨,达赖喇嘛具有了永恒存在的神性。

印度的一些抉择者有两种想法:一种认为,喜马拉雅地区佛教化,或者说藏传佛教化,可能更有利于印度的控制,所以他们会在印度政府与达赖喇嘛之间建立很多联系。还有一种认为喜马拉雅地区的藏传佛教化,甚至更进一步,即喜马拉雅地区达赖喇嘛化,这样就有了不确定性。也就是说,印度就不确定如果有一天达赖喇嘛成了问题,那么喜马拉雅地区会怎么办?所以有些人会认为喜马拉雅可以藏传佛教化,但是喜马拉雅不应该达赖喇嘛化。过去在流亡西藏社区里,学校和寺院里的流亡藏人与喜马拉雅地区的人是分得比较清楚的,我们是藏人,你们是喜马拉雅地区的人,但现在由于中国对边境的限制,从境内藏地来的学生和僧人越来越少,另一方面,从喜马拉雅地区来的人越来越多,而学校和寺院的教育体系都是藏文化的、藏传佛教的,所以这次这个事件会在喜马拉雅地区激起这么大的反应,这是必然的。意识不到这一点显然是错的。

中国就更不用说了。中国的决策者都是汉人,他们想利用这件事来攻击达赖喇嘛,完全错了。我认为中国政府犯了一个很大的错误。他们不了解宗教的影响力,不了解信仰的力量。他们只是非常粗暴的,非常简单的,用自以为是的方式来处理这件事。

而西方人对达赖喇嘛的了解,这些年已经不像以前那么多,只是听说达赖喇嘛的名字而已。我观察了很多西方人的网站,与藏传佛教有关的十几万人的网站,当这件事发生后,他们说我十几年前见过达赖喇嘛二十几年前见过等等,但是已经慢慢地忘了,于是另一个动力出现了,他们想了解达赖喇嘛是谁,他的思想是什么样的?随着了解,他们认识到原来他是无辜的,反而他们会支持达赖喇嘛。如果达赖喇嘛以前犯过一个错误,现在又犯第二次错误的话,那就会被西方人认为是污点。但是达赖喇嘛没有错,如果解释了可你还不接受的话,那就不是达赖喇嘛的问题,而是那些人的问题。当然有不少年轻人不了解,他们容易受网络宣传的影响,但也很快就会被新的热点所吸引。

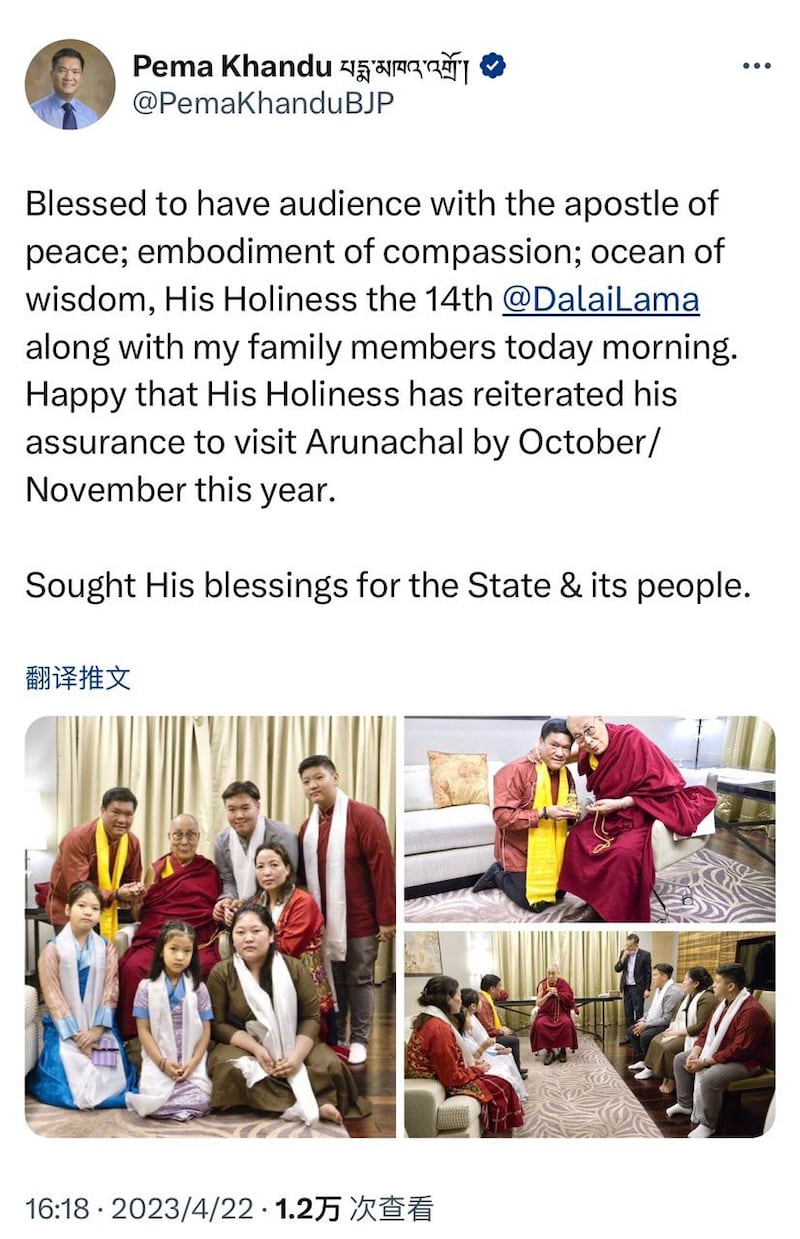

我:4月20日至21日在德里举办首届全球佛教峰会,尊者19日坐飞机去的。当天达兰萨拉下大雨,一大早天还没亮尊者就乘车去机场了,许多人捧着哈达冒雨相送。20日,尊者在酒店休息了一天。昨天是参加大会并做了发言。今天就回达兰萨拉了,这个时间很紧的。我从网上看到嘉瓦仁波切从德里回到达兰萨拉,无数藏人排队迎接,载歌载舞,场面感人,就好像达兰萨拉是我们的一个家那种感觉,其实是异国他乡,但现在是一个家,一个圣地。而这当然是因为尊者的缘故。

而在德里举办的首届全球佛教峰会很重要,这个重要性让我觉得可能也是为什么污名化尊者的事件,会在这个时间发酵。说不定是跟这个会有关,因为有些人可能想制造障碍。

昨天看全球佛教峰会上嘉瓦仁波切讲话,相信很多人都很高兴。很明显,虽然尊者的年纪越来越大,已经八十八岁,但他的思维是敏捷的,经文是大段大段的背,几十分钟的讲话根本无须看稿。完全没有任何退化之说,他的智慧是非常了不起的。而在峰会上也是众望所归,大乘小乘金刚乘的那么多高僧大德,还有那么多学者,这场景就像经书里记载的佛陀与众多菩萨在一起那样美丽非凡。其中一段话给我的印象深刻:“乍看之下,就以我们西藏的现况而言,确实是步履蹒跚、寸步难行。然而,若能以菩提心与空正见,懂得违缘转为道用的话,愈多的违缘,所带来的是愈高的智慧与经验值,愈能于成佛之道接近果位。所以法友们,务必加强思惟菩提心与空正见,这点很重要。当您懂得如何将违缘转为道用时,等于去除所有的违缘。”

当然我一想起来还是生气。这个类似"他人即地狱"的世界,却需要尊者达赖喇嘛以八十八年及未来更苍老的人生付诸于全部的慈悲和爱,只能说这个自以为是的世界及无数傲慢世人不配得到他的付出。而另一方面,在这个世界几乎遗忘藏人的困境之时,尊者达赖喇嘛以这样的无辜受责的方式重新让世界"看到"图伯特,与此同时,让绝大多数藏人及信仰藏传佛教的佛教徒凝聚在一起,这不能不说是某种神奇,恰如一句藏语俗语:རྐྱེན་ངན་གྲོགས་ཤར། (坏事变好事),也如佛教里面经常讲的逆缘变成顺缘。而事实已经证明,一切业已反转。并且这次这个事件的出现,可能对未来深具密意,所以我赞同你说的,这不是坏事而是好事。

哦,我们已经聊了很久,要不就这样吧,我要整理的话也会是很长的。

朋友:好的,那就再见吧,天气真好啊。(完)

(2023/4/22对话,5/2-5/14整理,于北京)

(本文发表于唯色RFA博客2023.06.08:https://www.rfa.org/mandarin/pinglun/weiseblog/ws-05152023141126.html)